In the early thirteenth century Ashkenazic Jews living in Germany, Austria, Bohemia and other Germanic lands began to speak a dialect of low German that soon turned itself into a jargon of German and Hebrew with some old French and Slavic words also thrown into the mix. In earlier centuries during the lifetime of Rashi (Rabbi Isaac Yitzchaki, 1040-1105, Troyes, France) the Ashkenazic Jews of France spoke the vernacular tongue of the area – old French. The small Jewish community in England then spoke Chaucerian English interspersed with old French as well. Since the time of the Norman conquest of England much old French had already seeped into the English of the time. However, after the expulsion of the Jews from both England and France in the thirteenth century the Ashkenazim trekked eastward into Germany, Central Europe, Lithuania and Poland and eventually Russia. There they fully developed their own unique language, which soon became known as Yiddish – literally, Jewish. Based on German, Yiddish absorbed within its vocabulary many Hebrew words, biblical, midrashic and Talmudic phrases, Slavic and Polish words and a semi-sing-song intonation reminiscent of Jewish prayer and study melody. As a living language it constantly developed and expanded over the centuries.

Even though there were strong differences in dialect and pronunciation between Ashkenazic Jews living in these different countries, Yiddish became the universal language of Ashkenazic Jewry wherever these Jews were living or travelling. It achieved its own status as being “mamaloshen” – the beloved mother tongue of Ashkenazic Jewry. Yiddish also developed colloquialisms, sayings and wry comments on life and people – all almost untranslatable into any other language – that became its identifying hallmark. It is a language of nuance more than vocabulary. As a folk language possessing few rules of grammar and syntax Yiddish has an earthiness, sometimes even a touch of vulgarity to it, a true reflection of everyday Jewish life. There is also a certain melancholy in its phrases but paradoxically it contains much wry humor and bemused comments about human foibles and life generally. And its sayings and metaphors many times also remained as the only safe way to mock and ridicule the oppressors and enemies of the Jews and the difficulties of Jews living under foreign and hostile rule.

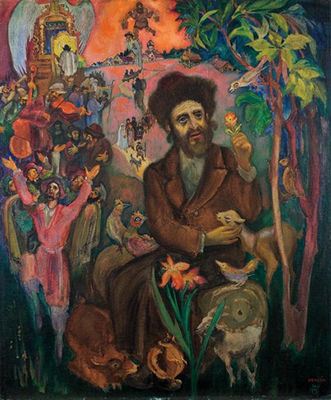

It was also the language of Torah scholarship and study, though the great works of Ashkenazic Torah scholarship were always written in rabbinic style Hebrew. Yiddish was too mundane and pedestrian for words of eternity. However, there were works of Torah knowledge written exclusively for women and children – holy storybooks, so to speak – that were written in Yiddish and were standard fare in Ashkenazic family homes for centuries. Rabbinic lectures, Talmudic discourses and Torah sermons were always delivered in Yiddish and the maggid – the itinerant preacher who travelled from community to community to exhort and entertain the masses – was usually a flowery and exclusively Yiddish speaker. Yiddish was the lifeblood of European Jewish communication, instruction and scholarship for many centuries.

Jews did not speak Polish, German, Lithuanian, Slavic languages or Hungarian amongst themselves for almost six hundred years. Only in the nineteenth century did this language situation begin to change. The change would be a severe and radical one. And the Yiddish language itself would become a focal battle point in this greater overall change and reordering of Ashkenazic Jewish society.

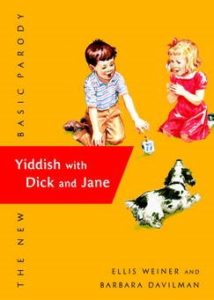

In the nineteenth century, due to the influence of Enlightenment/ Haskala, Marxism and incipient Jewish nationalism, many Jews began to define Jewish society no longer in terms of religion and Torah observance but rather in terms of “culture.” This idea of Jewish “culture” required a language with which it would be able to operate. Hebrew was too religious a language or later too Zionist a language or too holy a language to fit the bill for the emerging Jewish Marxist Left. The language had to be the lingua franca of the Jewish masses of Eastern Europe, but it also had to be capable of becoming the nucleus of this new Jewish “culture.” The “culture” people were almost all secular and even non-believing Jews but nevertheless Yiddish was chosen to be the official language of this new vanguard of Jewish society.

Yiddish newspapers, theater, literature, lectures, historiography, biblical translations and schools abounded. The YIVO Institute was established in Vilna to promote and encourage scholarship associated with the Yiddish language. It later relocated itself in New York. The Yiddishists pinned all their hopes on the triumph of Yiddish being accepted as the cultural and newly modern language of the Jews in Eastern and Central Europe. The very powerful, anti-religious and atheistic Jewish labor union, the Bund, championed Yiddish as the sole permissible language for the Jewish workers’ society. So, did the Marxists who recognized Yiddish as being a “proletarian” tongue in contrast to Hebrew, which was arbitrarily judged to be a “bourgeois” and anachronistic, nationalistic language.

The Yiddishist schools all over the world, the Peretz schools, the Shalom Aleichem schools, all preached the political doctrines of the Left while proclaiming the Yiddish language as being the catalyst for the eventual triumph of “culture” and Marxism over Torah and Jewish observance in its society. The Soviet Union originally also promoted Yiddish as a recognized and approved language, though it was viewed only as being an adjunct to the Russian language. Hebrew was banned as a language of use or study in the Marxist paradise. In fact, all Hebrew words and spellings that existed in Yiddish had to be “Yiddishized” to meet official approval. This was done by completely phoneticizing the spelling of all words in Yiddish that were originally of Hebrew origin, many times in an exaggerated and even ludicrous fashion.

The Zionists fought back against Yiddish and fiercely defended Hebrew as the correct language of their “new Jew” that they were confident of creating. This was especially true in Israel. In fact, there was a period at the beginning years of the State of Israel that Yiddish theater, newspapers and language was officially and actively discouraged and shunned in Israel.

Though Yiddish was thus defeated in Israel it continued to be recognized in the late 1940’s as the “official” Jewish language in the Soviet Union. But even there, Stalin’s subsequent anti-Jewish programs and the continued suppression of Russian Jewry by his successors diminished the use of Yiddish in the Soviet Union. By the 1950’s Stalin and his later cohorts had also purged the Bund, the Yiddish schools and almost all of the leading Jewish Marxists. There was no one left to champion the cause of Yiddish as an accepted minority language. Therefore, by the 1960’s almost all Soviet Jews spoke Russian as their mother tongue and Yiddish in the latter decades of the Soviet Union belonged only to the elderly and even then, was used only privately at home. The heroic Jewish dissidents of Soviet Jewry were interested in Hebrew and Torah, not in the writings of Peretz and Shalom Aleichem.

After World War II the great proponents of Yiddish as the cultural language of the Ashkenazic Jew were gone. Cultural Yiddish was unable to survive the terrible turbulence of the twentieth century Jewish and general world. A Nobel Prize for Literature would still be granted to Isaac Bashevis Singer for his Yiddish works, but this was viewed as being more of a memorial prize to the language than an acknowledgement of its current vibrancy. However, many universities today offer courses in Yiddish language and literature. A large number of the students in these courses are non-Jews. But studying Yiddish in a university classroom is no different than studying Latin or ancient Greek at the same institution. It is more in the nature of studying the anatomy of a corpse, rather than examining a real live human being. It is obvious that whatever the future holds for the Yiddish language, it will not serve as the vanguard of a new secular Jewish people. That dream of the nineteenth century Yiddish proponents has evaporated in the heat of the disastrous events that overwhelmed Eastern European Jewry in the twentieth century.

Amazingly, a substantial part of the Orthodox world never abandoned Yiddish despite its intimate association with Orthodoxy’s sworn enemies, the Bund and the Marxist Left. The Orthodox educational establishment in the late nineteenth century and thereafter till our day mainly disregarded the study of Nach (the books of the prophets and Divinely inspired Jewish wisdom), Hebrew language and Jewish history because of the use of these subjects by the Haskala/Enlightenment as the basis for its cultural drive to create its version of the “new Jew.” But these sections of Orthodoxy somehow never abandoned Yiddish as their mother tongue.

Thus, today Yiddish exists as a very alive language, spoken and widely used in many of the yeshivot of Israel and America and in almost all the Chasidic communities and enclaves all over the world. In fact, in those communities Yiddish has been elevated to be a holy tongue and English and even modern-day Israeli Hebrew are viewed as being foreign languages to be used only when necessary on the street but not at home or in the synagogue or study hall. And there are many purely Yiddish- speaking schools now operating amongst these groups, again both in Israel and the Diaspora.

The Bund and Jewish Marxism and the secular Yiddishists are practically extinct today. Thus, most Yiddish speakers today are blissfully unaware of the existence and dominant influence of the Bund or the Marxist Left in Jewish life a scant century ago and what fealty to the Yiddish language then meant. They are unaware or willingly deny that Yiddish was not only the language of Talmudic study and Chasidic discourse, but it was also the language of militant anti-religion and even blasphemous ideas and publications. To these groups within current Orthodoxy, Yiddish is the holy tongue of their ancestors and any association of Yiddish with the strongly secular and Marxist elements of Ashkenazic Jewry of the last centuries has been consciously and deliberately erased from the memory of today’s younger Orthodox Yiddish-speakers. Thus, the staying power of Yiddish in the Orthodox Ashkenazic world is truly remarkable. Ironies always abound in the Jewish world!