There is a tendency in very wealthy families for some of the children to divest themselves of all business interests and become philanthropists. It was true in the Ford family, the Rockefeller family, and the Carnegie family. It’s almost like repentance for how the money was made. They try to give it back to the people.

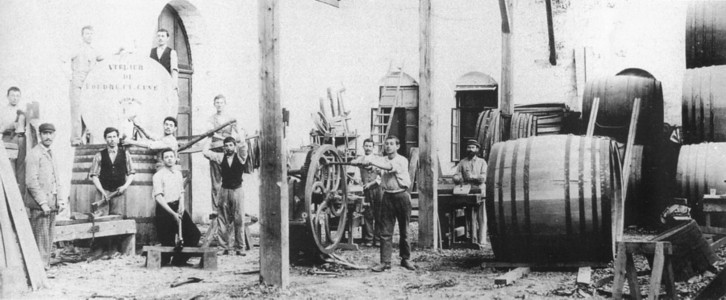

Baron Edmond de Rothschild of Paris was in his late twenties when he decided to become a philanthropist. During the Irish potato famine of 1847, he donated more money to the starving Irishmen than some of the most prominent families in Britain who actually drew their income from estates in Ireland, but what he wanted was a Jewish cause. How he found one goes to prove how life is stranger than fiction. Samuel Mohilever, a Yiddish-speaking rabbi from Bialystok, founded a movement called “the Lovers of Zion.” It encouraged Jewish settlement in the Holy Land, and this was well before Herzl’s political Zionism. He heard about the Baron and went to see him in Paris. I don’t know how they communicated. Rabbi Mohilever didn’t speak French, and the Baron didn’t speak Yiddish, but somehow Rabbi Mohilever got through to him, and the Baron invested millions in thirty-nine colonies in the Land of Israel, many of which are thriving cities and towns today – Rishon Le’tzion, Zichron Yaakov, Binyamina, Gedera, Rechovot. In 1882, he opened the Carmel Winery, which remains Israel’s biggest producer of wine. And the Rothschild Foundation continues to distribute millions each year to worthwhile causes.

Another outstanding Jewish philanthropist, a predecessor to the Baron, was Sir Moses Montefiore. His is not quite a rags-to-riches story, but it’s a combination of fortuitous events. He was born to a Sephardic Jewish family in London in the late 1700’s and was employed as a clerk in the banking house of Nathan Mayer Rothschild. There were no restrictions on insider trading then like there are today, so Montefiore got in on the action. He became an independent millionaire simply because the Rothschild wealth rubbed off on him.

When Montefiore became wealthy, he did a very noble thing. He dedicated the rest of his life to philanthropy on behalf of the Jewish people. Like the Baron, he was only in his twenties when he made this decision, and he lived to be 100, so for nearly 75 years, he acted as the representative of the Jewish people in places where no other Jew had influence. He was knighted by Queen Victoria and was a leading member of England’s aristocratic establishment. But he never forgot his Jewish roots, and like the Baron de Rothschild, used his wealth to build up the land of Israel.

There is a famous legend about Sir Montefiore. It is said that in the basement of his palatial home, he kept a coffin, and every night before he’d go to sleep, he’d put on his shrouds and lie in it for a while. He is reputed to have said that it was very good for eliminating arrogance.

Whether that story is true or not, the fact that such a story even exists about him shows us his character and how highly the Jewish people regarded him.

From the philanthropic accomplishments of these great men, we see that there’s no limit to the good that can be done with money. Unfortunately, there’s also no limit to the corrosion it can cause if misused or handled dishonesty. Wealth can be good, and it can be bad. It all depends on what you do with it.