I have recently completed reading two biographies about two very diverse but influential people. I will admit going from the ...

Read moreHis political opponents are either in Western exile or in Russian prison on dubious charges of tax evasion and money ...

Read moreIn an article in Commentary magazine, Professor Ruth Wisse wrote a very thoughtful article about anti-Semitism in our time. She ...

Read moreMay 1 was always the traditional day of commemoration and inspiration of the Socialists and Communists and their supporters and ...

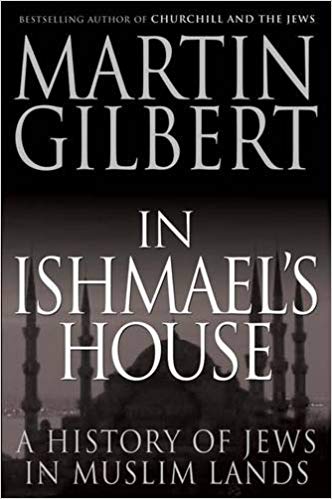

Read moreSir Martin Gilbert has written “In Ishmael’s House” a popular history of the Jewish experience over almost fifteen centuries of ...

Read moreRabbi Meir Shapiro The daf hayomi learning cycle of studying one page of the Babylonian Talmud every day was inaugurated ...

Read moreBobby Fisher in 1960 Bobby Fischer was perhaps the greatest chess champion of all time. He certainly was the greatest ...

Read moreThis is an “only in America” type of story. On January 11, 2009 the New York Giants professional football team ...

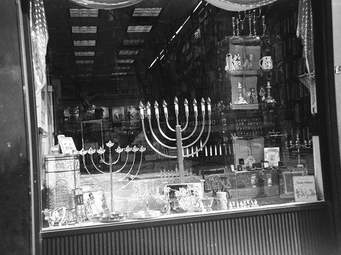

Read moreThe wonderfully joyous holiday of Chanuka occurs this month. In light of the horrific events of the past few months, ...

Read moreIn the early thirteenth century Ashkenazic Jews living in Germany, Austria, Bohemia and other Germanic lands began to speak a ...

Read more