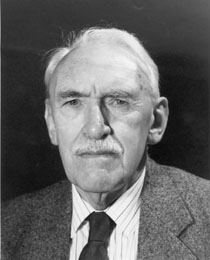

David Mamet is a Pulitzer Prize winning Broadway playwright as well as a well-established Hollywood movie script writer. His book, “The Wicked Son – Anti-Semitism, Self-Hatred and the Jews,” is a polemic against Jewish self-hatred. It is a powerful book and Mamet takes no prisoners.

He states his case as follows: “To the Jews who, in the sixties, envied the Black Power Movement; who in the nineties envied the Palestinians; who weep at Exodus but jeer at the Israel Defense Forces; who nod when Tevye praises tradition but fidget through the Seder; who might take your curiosity to a dogfight, to a bordello or an opium den, but find ludicrous the notion of a visit to the synagogue; whose favorite Jew is Anne Frank and whose second favorite does not exist; who are humble in their desire to learn about Kwanzaa and proud of their ignorance of Tu Bishvat; who dread endogamy more than incest; who bow their heads reverently at a baptism and have never attended a bris – to you, who find your religion and race repulsive, your ignorance of history a satisfaction, here is a book from your brother.”

Mamet recognizes that there is no one book that will convince these people of their recklessness, self-hatred and apostasy. He writes: “It is unlikely that any self-professed antagonist to Israel, and so to the Jews, can be brought by force of outside reason to recognize and correct their self-serving apostasy.”

But Mamet writes for the committed Jew and for the millions of Jews who like to be Jewish but just don’t know how to go about it. The remedy that he himself espouses is ritual observance and thus belonging to a large and ancient people who have an unbroken chain of tradition and historic achievements. No people can satisfactorily survive without a ritual and sense of belonging.

Mamet is a Reform Jew but he is a Reform Jew who takes Jewish beliefs and ritual seriously and studiously. In this he represents a slowly growing trend within the Reform movement of Jews who want and demand more tradition and ritual and less liberal social agendas and guitar playing services in their temples.

Mamet compares the alienated Jew trying to come back to his soul and roots to the challenges of a good actor performing on stage: Say the lines exactly as they are written. Try observing religious rites and allow them to lead you back to the theme of the play. Go to the synagogue and search there for a haven of belonging, learning and mutual support.

Jewish self-haters are not restricted to the Diaspora. The avant-garde in Israel despises religious Jewry for its crime of somehow not disappearing and for the temerity to be not just hanging on here in Israel but actually visibly expanding and growing. It blames Jews, Judaism and Israel for all of the faults and ills of the world. It sympathizes with our enemies, being blindly unaware that they too, as Jews, are in the crosshairs of those who would wish to destroy us.

Mamet’s book should be translated into Hebrew and distributed free of charge. His concluding words about being a Jew ring true with prophetic resonance: “We are the children of kings and queens, a holy nation and a kingdom of priests. We are the children of a mystery that has not abandoned us and that has come for us; it is both described and contained in the Torah.”

Mamet has said all that is necessary to be said. The rest is to go and study and practice.